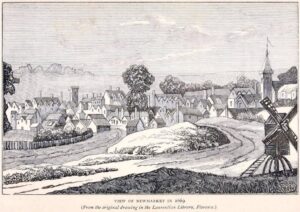

Newmarket’s Origins

Notes provided by N.L.H.S Chair Sandra Easom.

Mention Newmarket and most people think of the pounding hooves of horses and rolling expanses of green turf. The town is justly famous for both of these but it’s very long and varied history goes far beyond what most people expect.

Unlike most mediaeval towns, Newmarket is not centred on either of its parish churches, St. Mary’s or All Saints’. Rather, it is centred on the initial reason for its existence – the ancient Icknield Way – the oldest road in Britain. Its original route followed Palace Street, past All Saints’ Church and across the present-day cemetery. The Icknield Way also took other courses, notably through Stetchworth and Woodditton. People have journeyed along the Icknield Way since the Stone Age when flint was mined in Grimes Graves in Norfolk and then supplied an extensive trade network.

The area where Newmarket now stands has springs of water and a small river which is essential for any settlement. Bronze Age barrows, showing evidence of early occupation, were scattered across Newmarket Heath until the 19th century when they were cleared to make better conditions for horse racing.

Later, nearby Exning was a main settlement of the Iceni tribe (best remembered for their famous Queen Boudicca or Boadicea who led a major rebellion against the Romans). The Iceni were renowned breeders of horses and dogs, so the Heath has probably seen many more races than we are aware of!

The area where the town now stands was given as dowry to Sir Richard de Argentein in 1200 A.D. when he married Cassandra, daughter of Robert de Insula, Lord of the manor of Exning. Sir Richard encouraged development of the town and was granted a charter for a market almost immediately by the King.

In 1223 Newmarket received its first charter for an annual fair. It is important to note that the Plague arrived at Exning in 1227. Therefore, the Victorian theory that people left Exning to start a new town at Newmarket at this time cannot be true (although it is very persistent!).

Newmarket thrived because of its market and a lucrative trade in accommodating travellers and so it continued for centuries, until King James I “discovered” its Heath in February 1604 as a great leisure venue for his court and Newmarket’s sporting associations began…

Newmarket’s Medieval Market

By Sandra Easom, MSc

For over 800 years, since 1200 A.D., a general market has served Newmarket and the communities around it. This means that Newmarket’s medieval market is one of the oldest in Suffolk and perhaps, in the entire country.

Newmarket, as a community, was here long before the market gave the town its medieval name. The ancient Icknield Way runs through the town, and it also has its own water sources, essential for any ancient habitation.

Local archaeology also demonstrates that people have Lived around here for millennia. However, after the Norman conquest in 1066, the whole area was divided and became part of Exning manor to one side of the Icknield Way and part of Woodditton manor to the other side.

During the reign of King John (1199 – 1216 A.D.) market trade expanded across the country, and it increasingly became formalised under the control of the Crown. A Royal Charter had to be granted for any new market to exist and this also governed the days on which it could legally be held. Traders often travelled on from one market to another, so another consideration was whether other markets were held nearby? A community’s economy had to be protected. Consequently, official markets were only permitted to exist roughly a day’s journey apart from each other (13 – 15 miles).

So, how did Newmarket get such an early market charter? The land passed into the hands of Sir Richard de Argentein, an important and powerful man, around 1200 and it then became a manor in its own right. Apart from being lord of the manor, over time Sir Richard became Sheriff of Cambridgeshire, Huntingdonshire, Essex and Hertfordshire. He also owned another manor at Halesworth in Suffolk. Sir Richard would have easily obtained a market charter from the King.

Newmarket presented excellent financial opportunities to its lord because of its position on a main highway which combined with pilgrims’ and traders’ routes. The market, and the accommodation that Newmarket provided for travellers, also contributed to a thriving economy for the town. Of course, Newmarket’s residents were also farmers who grew food and brewed ale. They were able to trade these and other commodities because they were freemen and were not tied to the manor as people were in Exning.

By 1472 the market was large enough to be arranged in rows (a design still seen in Norwich market today). The rows then contained different, specialised trades and goods. Official records provide totals of 102 different shops and stalls. Its importance to the area is shown by the fact that the market had its own court of law, concerned purely with market matters.

Shops and stalls were rudimentary structures. Often, the front wooden shutters of a house were let down to form a counter or basic wood and fabric stands were unfolded. However, the placement of the shops and stalls was precise and measured. Two bailiffs supervised the market and fines were issued for any encroachment on un-rented land. Of course, the rents and the fines were paid to the lord. Stallholders could hire the same place for years and even passed the right to rent it to their children.

During its long history, the market has relocated several times. The High Street and The Rookery have been favourite locations. In fact, a market cross once stood in the High Street. Later in Newmarket’s history a corn exchange was added to the market and a cattle market also stood behind The Waggon and Horses pub. Many market animals arrived by train from Victorian times until the early 20th century.

Until 2018 the most recent market relocation, from the High Street to the Market Square, occurred in September 1975, when many changes occurred simultaneously in and around Newmarket. These included the demolition of the old Rookery area and the building of the new shopping centre together with the opening of the new Newmarket bypass.

What of the old, but persistent, myth that Newmarket sprang up after the plague caused the market to relocate from Exning? This was first the theory of a Victorian vicar of Exning, Thomas Dibdin, formed in the absence of any other evidence. His theory was repeated in several contemporary directories and so became rooted as “fact”.

Following its market charter, Newmarket was granted its first fair charter in 1223. However, as the plague came to Exning in 1227, relocation of some of the population to Newmarket at that time is possible.

The lord of the manor of Exning applied for, and was granted, a market charter in 1257. This was probably because he had seen the success of his neighbour’s market. This new charter would not have been needed if an Anglo-Saxon market had already existed. No records appear to support any use of the Exning market charter.